This morning, I got a super early start on my writing work.

Like, super early — the birds were only beginning to chirp, their nests still shrouded in complete darkness.

I like to think, largely because of all the sacrifices I have had to make, that it’s all making a difference. That it will matter someday that I have chosen to persist and create and go after the idea of authorhood.

But maybe I’m just fooling myself.

Maybe I could have been just as happy singing in obscure coffee shops, living off the grid planting pumpkins or something else that doesn’t know how to contain itself, or shooting myself into space until I felt small and wanted to go home again.

I don’t really know the “best” path

The choices or paths I suggest above are not bad. But there’s nothing to really say I ought or ought not to have taken them. I don’t know what might have been if I had done differently and opted to take one of them. In that sense, they are bathed in equality that makes identifying and selecting the “best” path ridiculous.

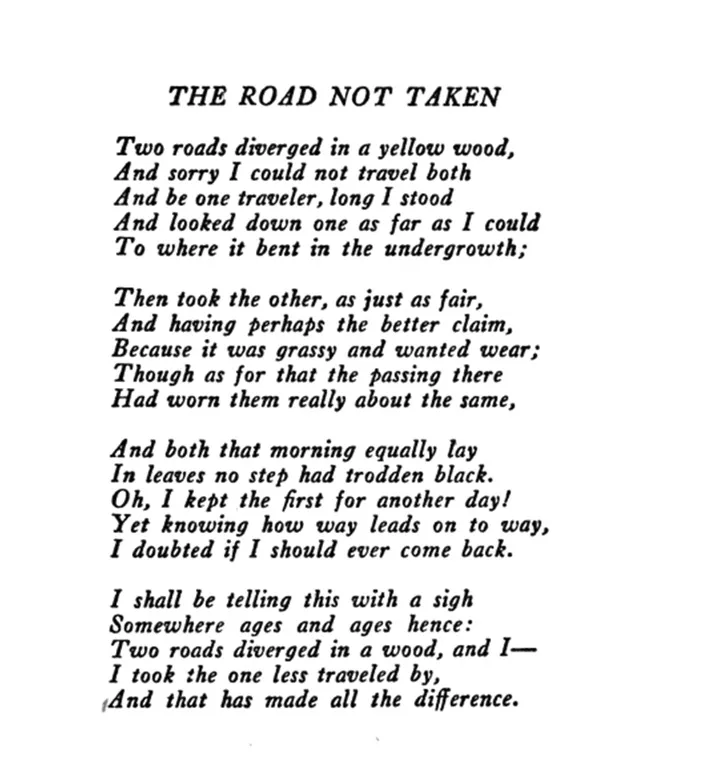

This is the heart of Robert Frost’s famous — and wildly misunderstood — poem, The Road Not Taken.

The poem is often championed as a testimony to our own capacity to make decisions and think for ourselves — our choices make all the difference.

But as the Wise Hub Medium blog notes, we can see down potential paths only so far. There’s always uncertainty about what the influence of selecting a choice will be because of that. We don’t actually know in the moment whether one option is any better.

“…the traveler in the poem, like each of us in life, cannot discern what lies beyond the choice’s immediate bend, as Robert notes: “To where it bent in the undergrowth.” The only way to truly understand what the path holds in store for us is to tread upon it, and once we´ve done this, our choice has already been made.“

Frost’s intent

Frost did not write the poem as a testimony to independence or autonomy. He in fact wrote it as a friendly but truthfully convicting observation on the habit of his good friend, Edward Thomas. When they would walk together, Thomas frequently would show indecisiveness about which way to go. Frost’s poem is an acknowledgement how people tend to create their own self-narratives and, in the process, don’t allow that their decisions might have factored very little — or not at all — in getting them where they currently are. As David Orr writes in The Road Not Taken: Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong:

Most readers consider “The Road Not Taken” to be a paean to triumphant self-assertion (“I took the one less traveled by”), but the literal meaning of the poem’s own lines seems completely at odds with this interpretation. The poem’s speaker tells us he “shall be telling,” at some point in the future, of how he took the road less traveled by, yet he has already admitted that the two paths “equally lay / In leaves” and “the passing there / Had worn them really about the same.” So the road he will later call less traveled is actually the road equally traveled. The two roads are interchangeable.

According to this reading, then, the speaker will be claiming “ages and ages hence” that his decision made “all the difference” only because this is the kind of claim we make when we want to comfort or blame ourselves by assuming that our current position is the product of our own choices (as opposed to what was chosen for us or allotted to us by chance). The poem isn’t a salute to can-do individualism; it’s a commentary on the self-deception we practice when constructing the story of our own lives.

Lamenting over your choices is not necessary

My intent now is not to wag a finger and tell anybody they ought to know better and interpret Frost properly. In America’s desperate cloak of capitalism and grit, it’s hard not to misinterpret the poem — the final two lines align with perfection to the nation’s values and overall attitude around life crafting. I can understand how, hearing this American message so many times in so many different places, our brains would have trouble interpreting Frost’s words for what they really are, as they go so hard against the learned pattern.

I don’t mean either to say that, if everything is just a constructed narrative, that everything is meaningless.

Rather, my intent is to note that,

if our choices do not have as much weight as we would like to believe, then perhaps we ought not to get lost in lamenting over them. Perhaps, instead of stressing out over what to do, we ought to merely take a step and see what happens. “Let me see” might be better than “I must.”

There is value in having a simple curiosity around life. In that sense, there is no wrong path. We will learn and experience something no matter which way we are moved or choose to go forward.

That, to me, is a relief.